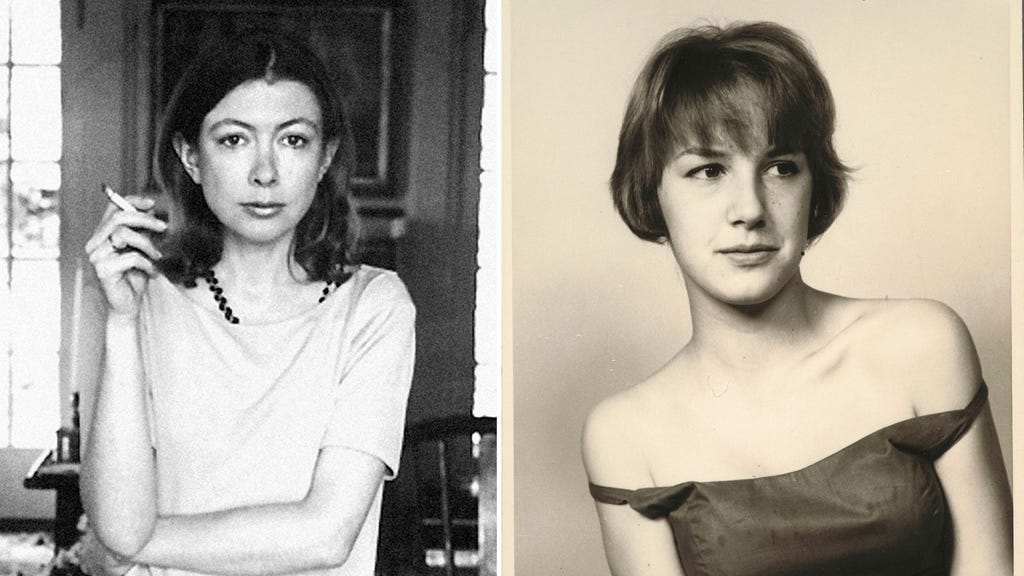

The literary world mourned the passing of Joan Didion in December 2021, her iconic sunglasses and Le Creuset cookware fetching exorbitant prices at auction, her Upper East Side apartment listed for $7.5 million. Simultaneously, across the country in Los Angeles, Eve Babitz’s sister, Mirandi, sifted through the remnants of a life lived in relative obscurity amidst a cluttered, decaying Hollywood apartment. Within this chaos, a discovered box of letters, notes, and diaries revealed a hidden gem – a scathing, unsent letter from Eve Babitz to Joan Didion, dated October 1972, a testament to a complex and compelling relationship between two literary giants.

The 1970s Los Angeles literary scene, centered around Franklin Avenue where Didion resided with her husband, John Gregory Dunne, provided the backdrop for this dynamic. A melting pot of art, music, and literature, the scene pulsed with creative energy and excess, attracting luminaries like Harrison Ford, Michelle Phillips, and Julian Wasser. Amidst the parties and intellectual fervor, Didion’s star ascended with the publication of ”Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and ”Play It As It Lays,” cementing her status as a literary icon. During this period, Didion took a keen interest in Babitz, facilitating the publication of her first piece in Rolling Stone and offering to edit Babitz’s debut, ”Eve’s Hollywood,” a gesture revealing Didion’s recognition of Babitz’s talent.

The relationship, however, was fraught with tension. Babitz, the embodiment of Los Angeles bohemianism, viewed Didion’s disciplined, controlled persona as her antithesis. This dichotomy, as journalist and author Lili Anolik observes, resonated with many women who identified with either the ”Joan” or the ”Eve” archetype. Anolik, who gained access to Babitz’s discovered correspondence, including the unsent letter, explored this complex dynamic in her book, ”Didion & Babitz.” The unsent letter, a potent symbol of their strained relationship, serves as a window into Didion’s carefully constructed persona, challenged by Babitz’s pointed question: ”Skulle du kunna skriva det du skriver om du inte var så liten, Joan?” This jab at Didion’s petite stature, often emphasized by Didion herself as a source of underestimated power, reveals a raw nerve in their dynamic.

Babitz, a fixture in the Los Angeles art and music scene, moved through the world as an active participant, photographing album covers for Buffalo Springfield, The Byrds, and Linda Ronstadt, her life a whirlwind of creativity and romantic entanglements. In stark contrast to Didion’s stable family life, Babitz’s relationships with figures like Jim Morrison and Steve Martin further solidified her ”party girl” image, hindering her literary aspirations and denying her the serious consideration afforded to male writers with similarly vibrant personal lives. The growing divide between them was exacerbated by Didion’s move to New York, a betrayal in Babitz’s eyes, as she felt Didion catered to East Coast perceptions of Los Angeles, perpetuating stereotypes of superficiality and decay. This resentment, perhaps fueled by envy of Didion’s literary success, further strained their already fragile connection.

The rediscovery of Babitz’s work, spurred by Anolik’s 2014 Vanity Fair article, brought her writing to a new generation, her blend of autobiography, essay, and journalism resonating with contemporary literary trends. Both Didion and Babitz offer distinct yet intertwined perspectives on Los Angeles, a city built on manufactured dreams and shadowed by complex social realities. Didion, with her cool, analytical prose, dissected the city’s allure and its underlying anxieties, while Babitz, with her vibrant, immersive style, captured its energy and contradictions. Their contrasting styles, mirroring their contrasting personalities, offer a multifaceted portrait of Los Angeles, a city as captivating and contradictory as the authors themselves.

The unsent letter, a key piece in understanding the Didion-Babitz dynamic, embodies Babitz’s frustration with Didion’s critique of the women’s movement and her perceived abandonment of Los Angeles. Anolik believes the letter was never intended for Didion’s eyes but rather for posterity, a hidden message revealing the underlying tensions and unspoken resentments in their relationship. Their near-simultaneous deaths, just six days apart, adds a poignant coda to their intertwined narratives. As Anolik suggests, their connection, like yin and yang, found a strange symmetry in their finality, highlighting their interconnectedness despite their differences. Their contrasting approaches to life and literature ultimately enriched the literary landscape, leaving behind a complex and enduring legacy.