In November 1968, a group called ”Alternativjul” (Alternative Christmas) launched a campaign to ”Stop Christmas,” denouncing the holiday in its contemporary form as ”anti-human” and advocating for a boycott. They planned direct actions and sought alternatives to the perceived excesses of the season. Their efforts culminated in a demonstration in Stockholm a few weeks later, where hundreds of people marched through the December slush carrying signs with slogans like ”More community, less excess,” ”Free Santa,” and ”Stop the Christmas terror.” This activism wasn’t an isolated incident; the group had previously protested the Teenage Fair in Stockholm, redirecting youth from the commercial event to alternative activities. Their actions forced the fair to close early, but now their target was not a mere trade show, but the deeply entrenched cultural institution of Christmas itself. And they were not alone.

The ”Alternativjul” movement was part of a larger societal wave of anti-establishment sentiment. Other groups emerged with similar, albeit sometimes more radical, aims. ”Jul nu” (Christmas Now), for example, deemed Christmas ”capitalism’s orgasm” and sought broader societal change. Meanwhile, a group of Christian radicals formed ”Ny Jul” (New Christmas), lamenting the perceived erosion of the holiday’s religious significance. This diverse coalition of anti-Christmas sentiment found common ground in organizing alternative events. They hosted open houses at Konstfack, Café Mejan, and youth centers across Stockholm, offering free activities like painting, drawing, crafts, socializing, theatre, and music. Simple fare like soup, cheese sandwiches, and coffee replaced lavish Christmas feasts, and the homeless were offered shelter. These actions resonated with the broader social and political upheavals of 1968, a year often associated with widespread questioning of traditional norms and institutions, with Christmas serving as a prime target due to its perceived traditional, commercial, and bourgeois nature.

Students from Konstfack also joined the movement, inviting the marginalized – the homeless, single parents, and those struggling with addiction – to celebrate an alternative Christmas at the school under the banner of ”Stop the Christmas terror.” This collective effort provided a counterpoint to the perceived consumerism and exclusivity of the traditional holiday. The various groups, each with their own specific grievances but united in their rejection of Christmas as it was then celebrated, worked together to provide alternative spaces and experiences. These alternative celebrations offered a sense of community and inclusivity that contrasted sharply with the perceived commercialism and societal pressures associated with traditional Christmas festivities.

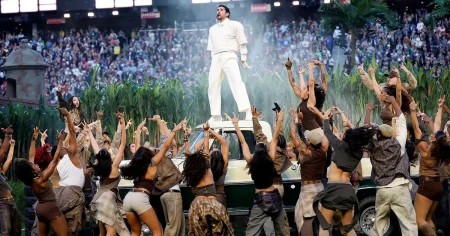

However, the fervor of this anti-Christmas movement proved fleeting. The following year, the protests subsided, and Christmas returned to its familiar form. Santa remained employed, and the holiday continued unabated. While subsequent protests, such as the ”Alternative Festival” during the Eurovision Song Contest held in Sweden, emerged with similar anti-commercialization themes, they failed to achieve lasting change. Neither Christmas nor the Eurovision Song Contest were dethroned, instead both continuing to grow in popularity and scale. The protests, though vibrant and representative of the era’s social climate, ultimately remained a ripple on the surface of deeply ingrained cultural traditions.

The meaning of ”alternative” itself has evolved over time. While still representing a departure from the mainstream, it no longer carries the same connotations of radical social critique. Today, an ”alternative Christmas” is more likely to involve a variation on the traditional festive menu or a different kind of celebration, rather than a wholesale rejection of the holiday. The focus has shifted from challenging consumerism and excess to embracing diverse experiences. Traditional elements like Christmas trees, twinkling lights, and gingerbread remain, coexisting with newer interpretations and additions. The spirit of rebellion has been replaced by a desire for novelty and personalization within the existing framework of the holiday. The current trend emphasizes choice and customization, allowing individuals to curate their own unique Christmas experiences.

This shift is exemplified by the contemporary dining scene, particularly in cities like Stockholm. Restaurants now offer a global array of Christmas-themed culinary experiences, from Italian and French to Asian, Lebanese, and Greek. Instead of rejecting the festive meal altogether, the focus is on expanding and diversifying the traditional Christmas menu. Establishments like Boulebar offer ”Christmas Boule,” combining the holiday with a game of pétanque, while Sjätte Tunnan provides a medieval-inspired feast. Brisket & Friends serve Texas BBQ, and La Botanica boasts a massive buffet featuring cuisine from ”all corners of the world.” These diverse offerings coexist with traditional Christmas elements, illustrating a move towards inclusivity and variety rather than outright rejection. Even workplace Christmas parties have embraced this trend, adopting themes like After Ski, Cowboy, Casino Royal, and Masquerade Ball, often with little connection to the traditional spirit of Christmas. This reflects a broader shift towards using the holiday as an occasion for socializing and entertainment, rather than specifically celebrating its traditional meaning. The author’s own experiences with a 1920s themed party and a Caribbean-themed Christmas party further highlight this trend towards novelty over tradition. The extended Christmas season, beginning as early as September with the appearance of Christmas soda in stores and encompassing the newly coined ”Novent” (November + Advent) and ”Black Week,” further demonstrates the commercialization and evolving nature of the holiday. While globalization has certainly played a role, the commercialization that activists once protested arguably fuels the ever-expanding and evolving nature of the holiday.