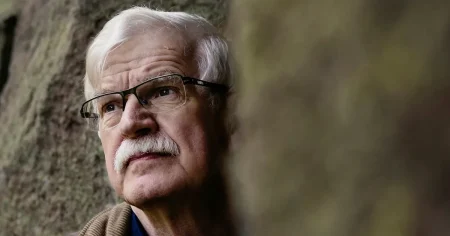

Gustav Bergström’s ”Tant Valborg bar alltid turban när hon gick bort” (Aunt Valborg Always Wore a Turban When She Passed Away) is a poignant exploration of a small village in Norrbotten, Sweden, serving as a heartfelt attempt to stave off the inevitable tide of forgetting. The book oscillates between capturing the essence of lived moments and meticulously documenting them for posterity, mirroring the tension Bodil Malmsten identified between life’s inherent chaos and the human impulse to archive and order it. With the older generation now resting in the village graveyard, Bergström takes on the mantle of the village chronicler, preserving the memories of their vibrant lives and idiosyncrasies, like the clatter of coffee cups during heated kitchen table discussions. He laments his younger self’s missed opportunities to fully engage with these ”originals,” recognizing the delicate balance between simply living and actively recording life’s tapestry. The core question emerges: who lives and who documents, and how do these roles intertwine in the preservation of collective memory?

Bergström, known for his expertise in building preservation, approaches his writing with the same meticulous care he applies to restoring old structures. Each detail, from his parents’ dinnerware to the vintage record player in his car, is rendered with an almost reverential attention, as if each element holds intrinsic value beyond its contribution to the whole. The book unfolds like a meticulous inventory, each item carefully cataloged and described. This painstaking approach initially resembles a dry archival process, yet it ultimately serves as a foundation upon which the vibrant stories of the villagers are built. This meticulousness, while occasionally bordering on excessive, creates a rich and textured backdrop for the human stories that form the heart of the book.

The true strength of Bergström’s work lies in the portrayal of the village inhabitants – Aunt Anna, Aunt Signe, Aunt Valborg, Alfred, Ivar, and the mischievous Stor-Klas. These are not caricatures of rural eccentricity, but rather individuals grappling with the tumultuous transition to modernity. A brief anecdote about a man stockpiling firewood, haunted by past experiences with hormonal herbicides and the looming threat of cancer, encapsulates both existential anxieties and the environmental consequences of progress. Similarly, the story of two sisters living on opposite sides of a mountain, forced to make expensive long-distance calls due to differing telephone networks, highlights the absurdities of technological advancement in a rural context. Bergström’s narrative skillfully weaves together personal anecdotes with broader historical shifts, creating a multi-layered portrait of a community on the cusp of change.

The book illuminates the conflicted emotions surrounding the march of progress. Bergström acknowledges the welcome relief from the hardships of pre-modern life, yet his own sensibilities are clearly drawn to the past. The tale of a farmer with artistic inclinations, struggling with agricultural tasks and harvesting late into the autumn, underscores the complexities of rural life and the diverse talents of its inhabitants. The inclusion of a story about a schoolteacher who began her career just as marriage restrictions for female educators were lifted serves to collapse the distance between different eras, creating a sense of traversing time. The book becomes a poignant reflection on the allure and the anxieties associated with embracing a new way of life.

However, the narrative falters when it shifts to the present day, focusing on Bergström’s own life and his restoration of barns on his family farm. This framing narrative, intended to provide a contemporary counterpoint to the historical accounts, becomes bogged down in excessive detail and a relentless self-focus. The meticulous descriptions of his daily routines, from brewing coffee to listening to vinyl records, lack the charm and significance of the village stories. This intense focus on the minutiae of his own life, presented with an almost self-important gravity, detracts from the overall narrative and feels jarring in contrast to the more engaging historical accounts. The constant documentation of his everyday actions feels less like genuine observation and more like an attempt to manufacture literary authenticity through an overabundance of mundane details.

Bergström’s tendency to portray himself as a figure of compelling interest, even in the most mundane aspects of his life, verges on self-indulgence. This relentless self-focus raises the question of what truly deserves to be documented from a human life. The overwhelming detail of his personal narrative, far from creating intimacy, ultimately distances the reader. This raises the central question for any memoirist: what details truly contribute to a compelling narrative, and which serve only to distract and diminish the overall impact? Despite this flaw, the book’s redeeming quality remains its touching preservation of the village’s collective memory. The vibrant stories of the inhabitants, brought to life through Bergström’s careful documentation, ensure that these individuals and their way of life are not completely lost to time, offering a valuable glimpse into a vanishing world. While the book’s contemporary framing narrative ultimately detracts from its overall impact, the heart of the story – the portrayal of a small village navigating the complexities of change – resonates with poignancy and provides a worthy tribute to a bygone era.