The author, Maria Andersson Vogel, a criminology docent and cultural writer, reflects on her weekend retreat at a convent, drawing parallels between the cloistered life and the modern prison system. Driven by a yearning for silence and introspection, Vogel sought refuge in the convent, a place where the external world fades, allowing for self-reflection and a re-evaluation of priorities. This isolation, coupled with structured rules governing daily life, mirrors the environment of a total institution, a concept developed by sociologist Erving Goffman. Although Goffman included convents alongside prisons and mental hospitals in his categorization of total institutions, Vogel acknowledges the distinct difference rooted in the voluntary nature of the former versus the coercive nature of the latter.

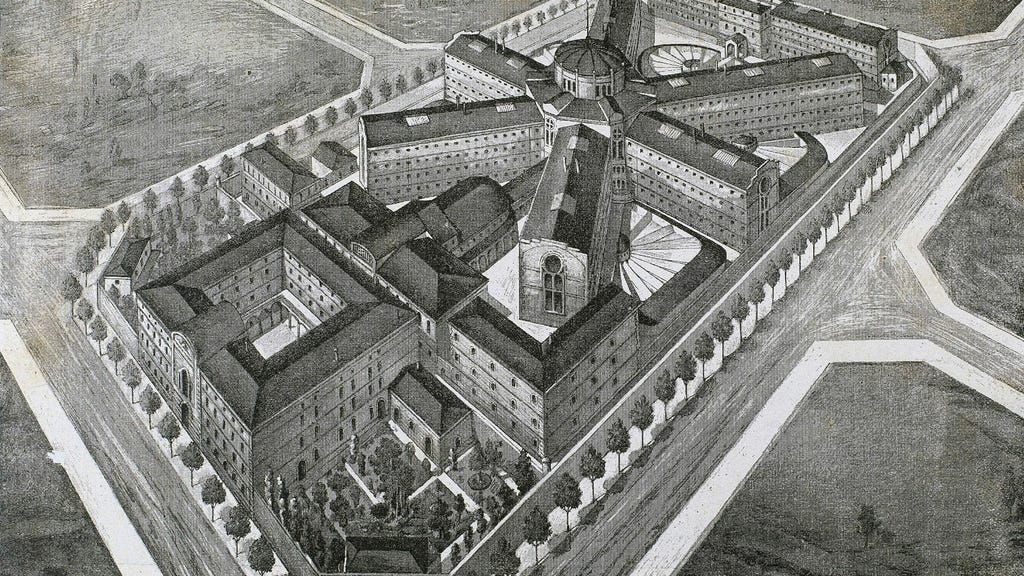

While seemingly disparate, Vogel posits that monasteries and prisons share surprising similarities in their structural design and daily rhythms. Both environments emphasize seclusion from the outside world, a regulated schedule interspersed with periods of solitude and communal activity, and a strict adherence to established rules. This comparison is further anchored in the historical evolution of the modern prison system. Emerging from the Enlightenment, modern prisons replaced corporal punishment with incarceration, emphasizing rehabilitation as a core principle. Inspired by the monastic model of solitary cells and spiritual reflection, the penitentiary, deriving its name from the Latin word for repentance, aimed to cure criminals of their perceived moral disease. This intertwining of religious ideals and Enlightenment rationality in the early prison system highlights a fascinating convergence of seemingly opposing forces.

Peter Scharff Smith’s research underscores the significant role of Christian thought in shaping the rehabilitative ideals of the early prison system. The belief in the possibility of moral reform through isolation and religious guidance led to the development of isolation prisons, where inmates were kept apart, their only human contact being with the prison chaplain. This extreme isolation, however, often resulted in mental illness rather than the intended spiritual and moral transformation. The author contrasts her own experience of peaceful solitude in the convent with the damaging effects of forced isolation in these early prisons. The key difference, Vogel notes, lies in the voluntary nature of monastic seclusion versus the imposed confinement of imprisonment, a distinction Goffman also recognized in his categorization of total institutions.

The critique of the modern prison system, gaining momentum in the 1960s and 70s, focused on the detrimental effects of incarceration. Despite the emphasis on rehabilitation, recidivism rates remained stubbornly high, suggesting that the negative impact of confinement outweighed any potential benefits. Scholars like Foucault, Scharff Smith, and Roddy Nilsson argue that the focus on rational control and discipline overshadowed the rehabilitative goals, ultimately transforming prisons into instruments of punishment rather than places of reform. The extreme isolation, intended to prevent negative influence between inmates, often led to mental breakdown instead of self-reflection and positive change. This paved the way for a reassessment of the prison system and its effectiveness in achieving its stated goals.

Vogel points to a more recent example within the Swedish prison system that more closely resembled the monastic model: a now-defunct program based on the Ignatian spiritual exercises developed by the founder of the Jesuit Order, Ignatius of Loyola. This program offered inmates a pathway toward self-discovery, repentance, and reconciliation with their past through structured retreats. The focus on introspection, coupled with open communication and the building of trust with staff, fostered a more supportive environment that differed significantly from the typical hierarchical and detached prison setting. The success of this program, according to Vogel, suggests a potential for incorporating principles of self-reflection and spiritual growth into rehabilitative efforts within the prison system.

The author argues that the now-discontinued prison monastery program might have come closer to the original ideal of the penitentiary: a place for contemplation, repentance, and transformation. This program, unlike its predecessors, managed to integrate the concepts of moral reform without succumbing to the overly rationalized and disciplinary approach that characterized early modern prisons. Vogel laments the abandonment of this program, particularly in light of current penal policies focused on expansion and stricter sentencing. Drawing on interviews with incarcerated women, Vogel highlights the potential for self-reflection and personal growth even within the confines of prison. The women’s testimonies echo the author’s experience at the convent, suggesting that moments of quiet introspection and the opportunity to confront one’s past actions can be valuable steps towards rehabilitation.

Vogel concludes by advocating for a more nuanced approach to rehabilitation within the prison system, drawing inspiration from the principles of monastic life. While acknowledging that monasticism is not a solution for every inmate, the core principles of the Ignatian retreat – introspection, responsibility, and reevaluation of past actions – hold relevance for broader rehabilitative efforts. Creating an environment that fosters both silence and meaningful dialogue, allows for personal reflection, and promotes trust-building relationships might offer a more effective path towards reducing recidivism. This, however, requires a shift in penal policy, moving beyond a purely punitive approach to embrace the possibility of genuine transformation. Vogel’s reflections underscore the need for a more humane and restorative approach to justice, recognizing the potential for individual change even within the seemingly unforgiving context of incarceration.