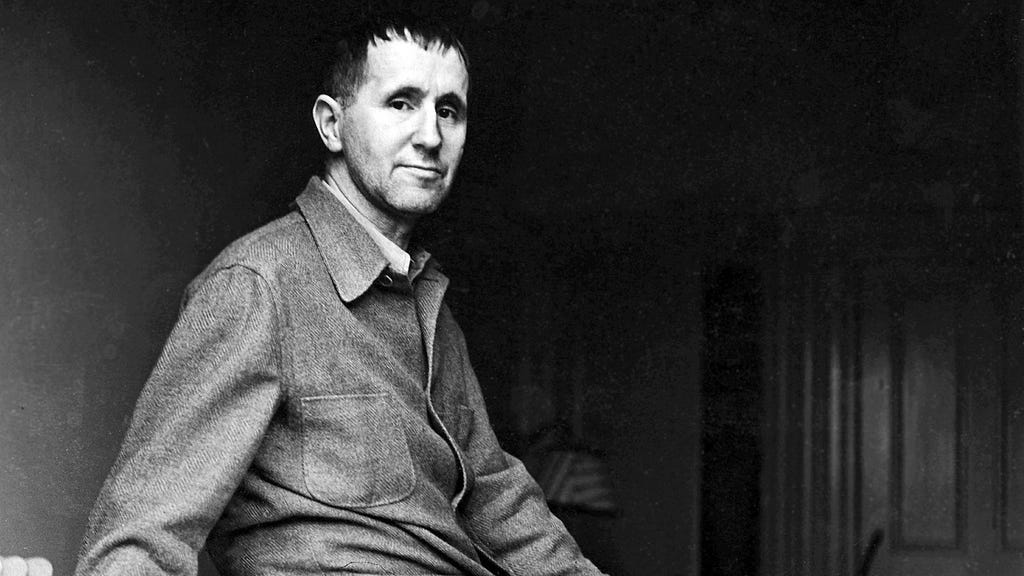

The legacy of Bertolt Brecht, the influential German playwright and poet, continues to spark debate, particularly regarding his complex relationship with Stalinism. Dramatist Martin Jonols recently criticized theatres for their perceived uncritical embrace of Brecht, citing the upcoming ”Brecht in Concert” at Kulturhuset Stadsteatern in Stockholm as an example. This concern, however, is not new; the question of Brecht’s political leanings has been a recurring theme in literary and theatrical discussions for decades. The core issue revolves around the interpretation of Brecht’s work, particularly his 1930 play ”Die Massnahme” (The Measures Taken), which some interpret as an endorsement of Stalinist purges.

”Die Massnahme” depicts four Soviet agitators who are brought before a party tribunal for killing a young Chinese comrade whose mistakes jeopardized their undercover mission. The play’s ambiguous nature has led to widely divergent interpretations, ranging from a classical morality play to a depiction of modern humanity’s entrapment by imposed choices. Literary scholar Rikard Schönström argues that the play’s theatrical framing prevents a straightforward endorsement of communist ideology, forcing the audience to confront the complexities of the situation rather than passively accepting it. Brecht’s “learning plays,” of which ”Die Massnahme” is an example, have been criticized from both sides of the political spectrum, with some Marxists finding them too idealistic and abstract, while others see them as disturbingly pragmatic. Schönström suggests that rather than viewing the play as pure propaganda, it should be understood as exploring the dynamics of political agitation itself.

Adding fuel to the debate is a chilling quote attributed to Brecht regarding the Moscow Trials: “The more innocent they are, the more they deserve to be shot.” This seemingly paradoxical statement can be interpreted as a veiled critique of Stalin’s regime, as the innocent are guilty only of not participating in the paranoia and conspiracies of the totalitarian state. This interpretation, championed by figures like Hannah Arendt, suggests a deeper, more critical understanding of Brecht’s position than a surface reading might indicate. The challenge, then, lies in disentangling Brecht’s artistic intentions from his personal political compromises and the historical context in which he operated.

Jonols’ critique extends to Brecht’s broader influence on theatre, lamenting what he perceives as a politicization of the art form, reducing drama to mere audience indoctrination. However, dismissing Brecht entirely would be a disservice to his significant contributions to theatrical innovation. Schönström highlights the influence of Japanese Noh theatre on ”Die Massnahme,” noting the use of masks, the chorus, narrative elements, and ritualistic aspects that foreshadow Brecht’s later development of the Verfremdungseffekt, or distancing effect. This technique, which encourages critical reflection rather than emotional immersion, has profoundly impacted modern theatre. Brecht’s influence can be seen in the work of contemporary playwrights like Roland Schimmelpfennig, whose ”post-epic” style has been described as ”Brecht on speed,” demonstrating the enduring legacy of Brecht’s experimental approach.

Brecht’s silence during the imprisonment of his friends in Moscow remains a troubling aspect of his biography. While it is tempting to condemn his inaction, it is perhaps more insightful to view Brecht himself as a character in one of his own plays, trapped within a system that limits his agency. This does not invalidate the power and relevance of his work, which continues to resonate with contemporary audiences. His poems, such as the one quoted by Jonols about self-censorship in times of oppression, force us to confront difficult questions about our own complicity in systems of power. Brecht’s legacy is thus one of contradictions: a brilliant innovator who made compromises, a critic of totalitarianism who remained entangled within its web.

Ultimately, engaging with Brecht’s work requires a nuanced approach. It demands acknowledging the historical context, recognizing the complexities of his political stance, and appreciating his undeniable artistic contributions. Dismissing him outright based on his perceived political failings risks overlooking the enduring value of his theatrical innovations and the unsettling questions his work continues to pose about power, complicity, and the human condition. The debate surrounding Brecht’s legacy serves as a reminder of the ongoing dialogue between art and politics, and the challenge of reconciling artistic expression with the complexities of lived experience.