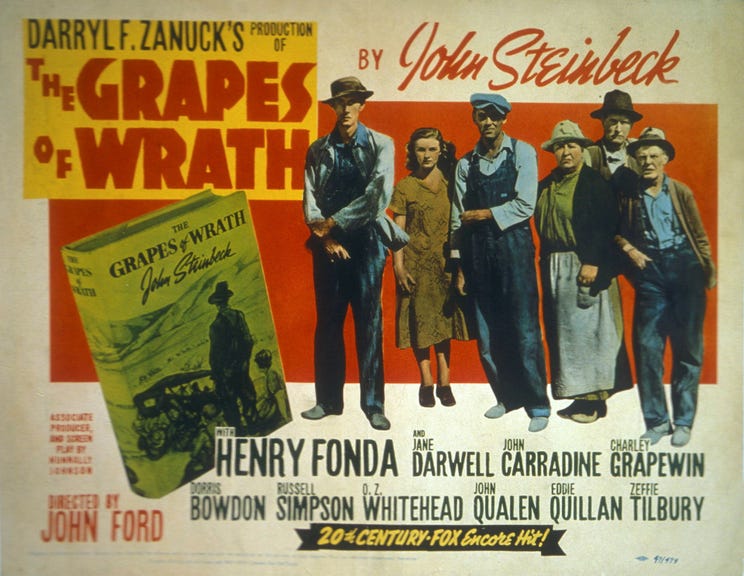

The 2016 US presidential election witnessed a surge of support for a candidate who employed racially charged rhetoric against immigrants, promising their expulsion, in states like Kentucky and Oklahoma. Ironically, these very states, situated on the geographical and socioeconomic periphery of America, were once the origin points for hundreds of thousands of impoverished migrants forced to flee the devastating Dust Bowl of the 1930s, a period of severe dust storms that decimated vast swathes of agricultural land across the American Midwest. These displaced families, driven by desperation, sought refuge and work in California’s fruit orchards, only to be met with exploitation and humiliation at the hands of ruthless growers and a capitalist-aligned law enforcement system. Derogatorily labeled “Okies,” they were vilified as dirty, dishonest, and unwanted. John Steinbeck’s epic 1939 novel, The Grapes of Wrath, immortalized this catastrophe, offering a poignant portrayal of their plight. The book’s immediate success, selling 400,000 copies in its first year and earning the Pulitzer Prize the following year, coincided with the release of John Ford’s iconic film adaptation, solidifying both the novel and film as enduring classics.

Dramaten, Sweden’s national theatre, recently staged a production of The Grapes of Wrath, commendably tackling timely themes of agricultural crises, soil erosion, and the resulting migration. However, the production opted for a timeless aesthetic, evoking the science fiction epic Dune, according to several reviewers. This artistic choice arguably detracts from the journalistic essence of Steinbeck’s work, which originated from his firsthand observations of refugee camps while reporting on the crisis. Steinbeck, a Californian himself, meticulously documented the tragic conditions, channeling his journalistic experience into the novel’s creation within a remarkably short five months. His work fiercely criticizes capitalism, bureaucratic indifference, and the ruthless destruction wrought by industrial agriculture on both the land and its cultivators – themes that remain strikingly relevant today, yet are often absent from public discourse.

Kentucky and Oklahoma are also the home state of J.D. Vance, the former Vice President, whose bestselling memoir Hillbilly Elegy paints a bleak picture of life in the region. Vance critiques his own background, portraying the residents as poorly educated, narrow-minded individuals trapped in a destructive culture of honor. He presents them as foolish individuals who, unlike himself, failed to ascend the social ladder from the periphery to the heights of Harvard, Wall Street, and ultimately, the upper echelons of American power. However, Kentucky also boasts a figure diametrically opposed to Vance in almost every respect, particularly in their views on rural America and its people: the 90-year-old writer, poet, essayist, farmer, cultural critic, and activist, Wendell Berry. Berry stands as a living symbol of resistance against what he terms "industrial fundamentalism."

Born amidst the devastating agricultural crisis of the 1930s, Berry, like Vance, left Kentucky for a promising career as a poet, writer, and academic in New York and Paris. However, at the age of thirty, he made a decisive return to Kentucky to embrace the life of a farmer. From his vantage point in rural America, Berry has, for six decades, issued warnings and condemnations against the dismantling of family farms, and the erosion of knowledge and connection to place. His 1977 book, The Unsettling of America, achieved widespread recognition and is now considered an American classic. Often mentioned in the same breath as Henry David Thoreau, Berry shares a similar moral stature and literary influence. While the fight against slavery was the central moral issue for Thoreau, Berry confronts the more complex systems of environmental degradation and the erosion of local communities, and their connection to the military-industrial complex. He argues that American militarism finds its domestic counterpart in the war against nature.

Berry highlights the parallel between modern warfare, directed by commanders geographically removed from the battlefield’s horrors, and the actions of large agricultural conglomerates. Their detachment from the land and its workers allows them to inflict massive damage on both, highlighting a geographical and moral displacement that fuels industrial society’s disregard for place and consequence. Berry champions the importance of place, of rootedness and intimacy with the local. His farm in Henry County, Kentucky, serves not only as his home and livelihood, but also as the foundation of his worldview—a deeply personal, practical, ideological, and even spiritual grounding. He vehemently critiques the destruction of rural life justified by supposed economic benefits. While mechanization, technology, and chemicals are touted as serving agriculture, increasing food production, and enhancing farmers’ competitiveness, Berry challenges this premise. He questions the very nature of competition in agriculture, asking: against whom? "We are forced to answer: against other farmers, at home and abroad."

In the era of climate catastrophes, it is crucial to recognize how natural disasters are often caused or exacerbated by human actions. The Dust Bowl serves as a prime example of a “manmade catastrophe,” as emphasized by renowned documentarian Ken Burns in his 2012 film The Great Plough Up – The Dust Bowl. Burns reveals how white settlers arrived in the fertile Great Plains, covered in deep-rooted grasses that sustained vast buffalo herds, enriching the soil. Despite the region’s harsh climate of cold winters, dry summers, and strong winds, the native grasses held the soil and moisture in place. However, in the late 19th century, white settlers displaced Indigenous populations and initiated the "great beef bonanza," laying the groundwork for today’s meat industry. The early 20th century saw unusually wet summers, prompting pronouncements of a permanent "climate shift," which lured impoverished migrants to buy or lease increasingly smaller plots of land. Encouraged by "experts" to remove the native grasses, they converted vast areas into wheat fields, driven by wartime demands and soaring prices. This industrialization of agriculture, fueled by debt and new technologies, ultimately led to the Dust Bowl’s devastation when drought returned, leaving the exposed soil vulnerable to wind erosion. The resulting dust storms decimated communities, causing widespread suffering and death. This pattern of unsustainable agricultural practices, driven by short-term economic gains and disregard for ecological realities, continues to be replicated around the world, highlighting the urgent need for a more sustainable and equitable approach to agriculture, one that prioritizes ecological balance and the well-being of both land and people. As Wendell Berry argues, a shift from a monologue of control to a dialogue of respect and understanding with nature is essential for a sustainable future.