Käthe Kollwitz’s artistic legacy, as showcased in a major exhibition at the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, is one of profound empathy, social commentary, and unwavering dedication to portraying the plight of the vulnerable. Her works, spanning over half a century, consistently depict the suffering of women, children, the poor, and the oppressed, capturing the human cost of war and industrialization with stark realism and emotional intensity. The exhibition, the first in Scandinavia in fifty years, traces Kollwitz’s artistic journey from her early depictions of historical worker uprisings to the bleak disillusionment of her final series, ”Death,” revealing a remarkable continuity of style and expression throughout her career.

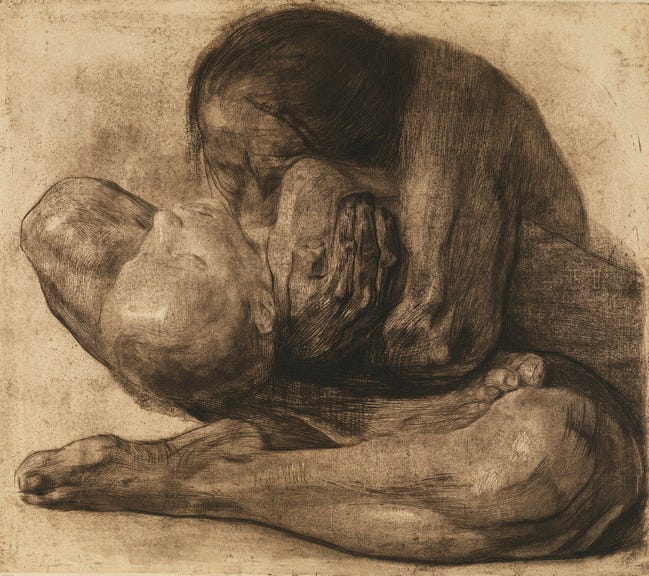

Kollwitz’s artistic foundation lay in drawing, which served as the basis for her explorations in painting, sculpture, and especially printmaking. While her works often display a delicate attention to detail, her distinctive style is characterized by expressive, monumental gestures and a profound sense of compassion. The recurring motif of the mother and the dead child, exemplified in early drawings of Peter, her own son, takes on a haunting, prophetic quality in light of his later death in World War I. This theme, revisited in various forms throughout her career, including the poignant ”Pietà” sculptures, embodies her preoccupation with loss, grief, and the devastating impact of war.

The exhibition highlights the remarkable consistency of Kollwitz’s artistic vision. From her early breakthrough with the ”Weavers’ Revolt” series, based on Gerhart Hauptmann’s novel about the Silesian weavers’ uprising, to her later, more explicitly political works, she consistently champions the marginalized and exposes the brutal realities of her time. The Copenhagen exhibition reveals the enduring power of these images, which resonate with a raw emotional intensity that transcends the specific historical contexts they depict. Her artistic language, forged in the late 19th century, anticipates the German Expressionism of the early 20th century while also echoing the social realism of artists like Goya and Géricault.

Kollwitz’s art is not merely a reflection of historical events; it is an active engagement with the social and political turmoil of her era. Her unflinching portrayal of suffering and injustice serves as a powerful indictment of war, poverty, and oppression. As Germany descended into the darkness of Nazism, her works became increasingly imbued with a sense of urgency and despair. The anti-war woodcuts of the 1920s, culminating in an image shrouded in black, and the numerous iterations of the ”Pietà” sculpture, with the mother’s body forming an impenetrable shield over her dead child, express the profound grief and disillusionment of a nation grappling with the horrors of war and political extremism.

Despite the overwhelming sense of despair that pervades much of her later work, Kollwitz’s art also possesses a captivating beauty, particularly evident in some of the earlier drawings from the Peasant War series. These works, while depicting scenes of violence and brutality, demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to detail, creating a stark contrast that heightens the emotional impact. One such drawing depicts a raped woman lying in a field, almost obscured by the surrounding vegetation. Only upon closer inspection does the face of a small child emerge from the dense foliage above, a detail that adds a layer of unbearable poignancy to the scene. This juxtaposition of beauty and horror, of delicate observation and brutal reality, exemplifies the enduring power of Kollwitz’s art.

Kollwitz’s profound impact on the art world stems from her unique ability to combine emotional intensity with social and political commentary. Her unwavering focus on the human condition, her unflinching portrayal of suffering, and her deep empathy for the marginalized make her work as relevant today as it was in her own time. The Copenhagen exhibition provides a comprehensive overview of her artistic evolution, showcasing the remarkable consistency of her vision and the enduring power of her images. From the early historical series to her final, deeply personal works, Kollwitz’s art remains a testament to the power of art to bear witness to history, to give voice to the voiceless, and to challenge the conscience of humanity. Her legacy is one of compassion, resilience, and an unwavering commitment to portraying the human condition in all its complexity and vulnerability.