Part 1: The Da Costa Case and Early Childhood Trauma Memories

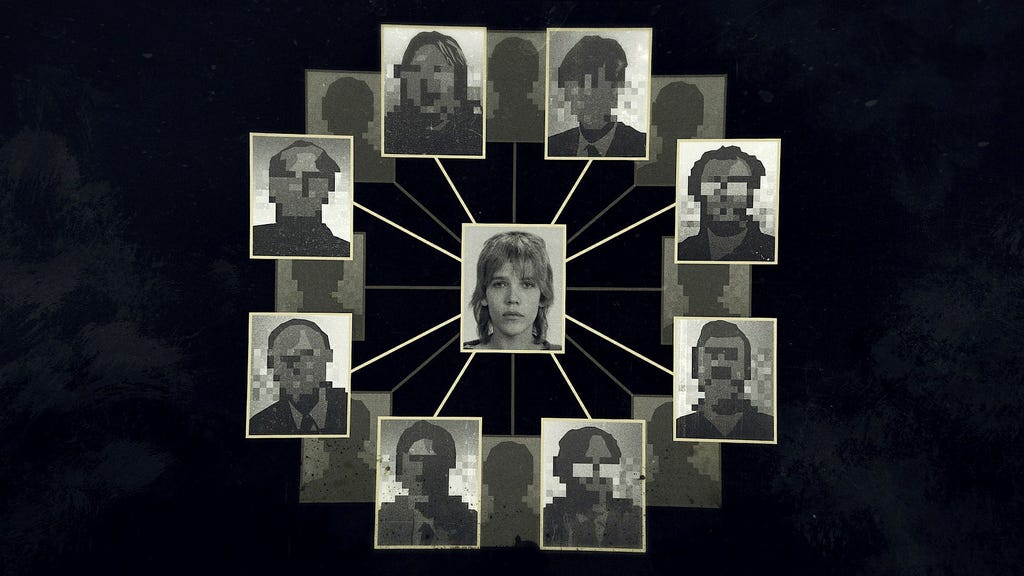

Dan Josefsson’s critique of the expert opinion provided in the da Costa case, concerning a young child’s potential memories of a traumatic event, is characterized by fragmented information, misleading inferences, and chronological inconsistencies. This detailed response aims to clarify the scientific understanding of how preverbal children process and potentially retain memories of trauma, providing context to the original assessment. The case centers around a girl who was approximately eighteen months old at the time of the alleged witnessed event (the dismemberment of a body) and around thirty months old when she began verbalizing expressions that could be interpreted as relating to the event.

Children who experience trauma after developing language, typically around two and a half to three years old, can generally describe the event verbally. Younger children, however, from around eighteen months, appear capable of storing internal images or other sensory impressions related to the trauma. These preverbal memories can persist for extended periods, and with language development, these sensory fragments can sometimes be expressed verbally, often triggered by associations later in life. Crucially, these fragmented memories do not typically develop into a cohesive narrative without external influence.

It is important to understand the nature of these early memories. They may not be static images but rather short, dynamic impressions, akin to short video clips. One memory fragment can trigger another, creating a false impression of a continuous recollection. Constructing a narrative from these disjointed fragments requires adult intervention, which introduces the risk of interpretation and suggestion.

Part 2: Behavioral Memories and Investigative Approaches

Beyond fragmented sensory impressions, trauma can also manifest in what are termed behavioral memories. These can include play that reenacts aspects of the traumatic event, specific phobias linked to the experience, and noticeable personality changes. In investigating potential trauma in young children, the primary focus should be on the child’s spontaneous utterances and play. Eliciting verbal expressions of a memory requires that the memory be actively present in the child’s mind. Questioning without such context is largely unproductive. Therefore, creating an environment that might trigger the memory is crucial. In this case, the psychologist introduced a camera into the play materials, responding to the girl’s expressed fear of a "photographer."

The documented interactions between the mother and child reveal a pattern of play that evokes potential associations to the trauma, followed by brief verbalizations from the child. For instance, the girl would repeatedly remove the limbs of a doll, then say things like, "Someone took away the lady’s head" or "She has no legs. They’re gone, and she can’t walk," which resonated with the details of the da Costa case. These fragmented utterances, characteristic of early trauma memories, did not develop into a coherent narrative, as predicted by existing psychological understanding.

The mother’s self-questioning and critical analysis of her own interpretations were not disregarded in the original assessment, but rather viewed as a demonstration of her thoughtful and reflective approach. This self-awareness was also evident in her described strategies for interacting with her daughter when themes of violence arose.

Part 3: Limitations of Recorded Material and External Influences

Josefsson’s review of the extensive recorded material did not uncover explicit confirmations of the girl witnessing the dismemberment. This is consistent with what one would expect, given the nature of the recordings. The mother, prompted by the police investigation, actively questioned her daughter seeking further details. While understandable given the circumstances, this approach carries the inherent risk of influencing the child’s responses and creating false memories.

It’s vital to distinguish between spontaneous recollections and responses elicited through questioning. The latter can be easily misinterpreted, particularly with suggestive questioning. The absence of a continuous narrative in the recorded material aligns with the theoretical understanding of fragmented memories in young children, rather than disproving the possibility of a traumatic experience.

Part 4: A Comparative Case Study and Theoretical Validation

A 2006 case study by a team of prominent US researchers provides a compelling illustration of the theoretical model of early memories and offers a parallel to the da Costa case. This case involves a young girl, Rachel, who witnessed her father murder her mother at approximately eighteen months old. The trauma involved a violent home invasion, gunfire, and the mother being shot while holding Rachel. The father subsequently committed suicide.

Rachel was raised by her grandmother, who chose never to discuss the event. Despite this silence, Rachel exhibited behavioral changes consistent with trauma: increased anxiety, sadness, developmental regression, and intense reactions to blood and the color red. Years later, at age four, during a fireworks display, Rachel cried out, "Stop shooting my mommy," demonstrating a clear activation of the traumatic memory, likely triggered by the loud noises.

Rachel’s case, where the trauma was well-documented and the child had no adult conversations about the event, approximates a controlled experiment. Her delayed verbal expression of the trauma, triggered by an associated stimulus, aligns with the theoretical model of how young children process and retain traumatic memories.

Part 5: Supporting Evidence and Legal Implications

The continued advancement of scientific knowledge in the field of trauma and memory further supports the conclusions and assessment made in the da Costa case. The theoretical framework, including the concept of fragmented sensory memories, behavioral expressions of trauma, and the influence of external questioning, provides a robust model for understanding the girl’s responses.

While the scientific basis of the assessment remains valid, its legal implications are a separate matter. In the da Costa case, the administrative court, while upholding the decision against the doctors involved, chose not to include the psychological assessment in its primary reasoning. This highlights the complexities of applying scientific understanding within a legal framework.

Part 6: Conclusion and Further Reflection

The da Costa case underscores the challenges of interpreting potential trauma memories in very young children. The scientific understanding of how these memories are formed, stored, and retrieved is crucial for any investigation. Focusing on spontaneous expressions, recognizing the fragmented nature of early memories, and avoiding suggestive questioning are essential to ensure accuracy and avoid misinterpretations. The case also highlights the complexities of using psychological assessments in legal proceedings, where different standards of evidence and interpretation apply. The ongoing development of scientific knowledge in this field underscores the importance of continued research and careful consideration of these delicate and complex cases.