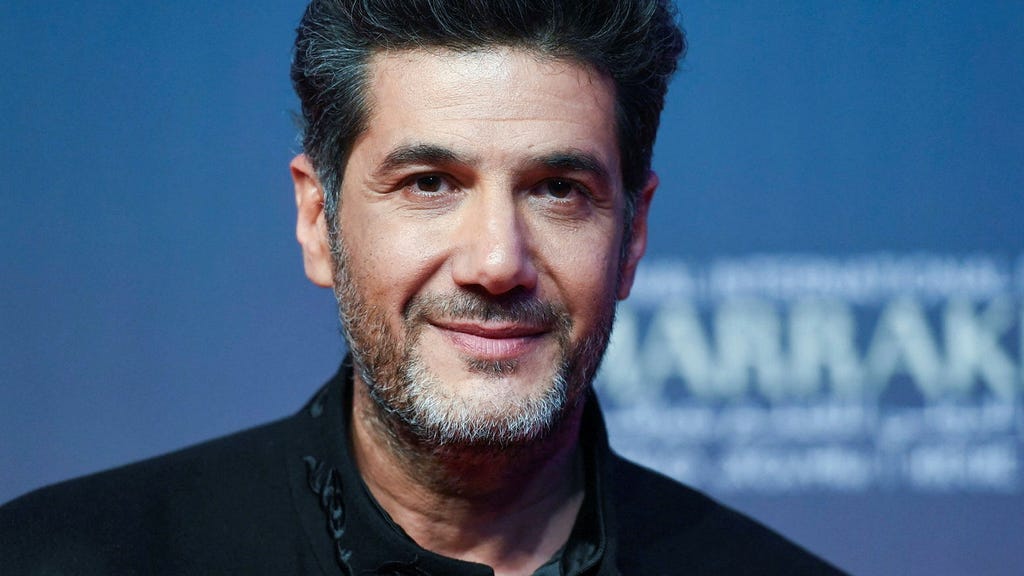

Nabil Ayouch, the French-Moroccan director celebrated for his socially conscious films, returned to the spotlight with his latest work, ”All Loves Touda,” 25 years after winning the Bronze Horse at the Stockholm Film Festival for his poignant street drama ”Ali Zaoua: Prince of the Streets.” Ayouch fondly recalled an encounter during that festival with Hollywood legend Lauren Bacall, sharing an anecdote of a wintry Stockholm walk and dinner, solidifying his image as a director who navigates both international film circles and the raw realities of marginalized communities. This juxtaposition of glamour and grit is a defining characteristic of Ayouch’s career, evident in his choice of subjects and his dedication to portraying them with both unflinching honesty and deep empathy.

”All Loves Touda” centers around the life of Touda, a Moroccan single mother navigating the complex and often contradictory world of sheikhas, traditional Moroccan singers whose lineage traces back to rebellious female poets. Played by the captivating Nisrin Erradi, Touda embodies the strength and vulnerability of these women, performing nightly in small-town bars while harboring dreams of stardom in Casablanca. Ayouch’s fascination with sheikhas stems from their powerful presence in Moroccan society, their ability to command attention and evoke strong emotions through their poetic songs. He highlights the injustice of their evolving public image, from revered heroines to being unfairly perceived as prostitutes, a transformation he seeks to challenge and rectify through his film.

Ayouch meticulously incorporates the sheikhas’ song lyrics into the film, emphasizing their historical and cultural significance. These lyrics, he explains, narrate the struggles against powerful rulers in the 19th century, the French protectorate, and the sheikhas’ crucial role in Morocco’s liberation. The evolution of their themes, from political commentary to explorations of love, desire, and the body, represents a subversive act in a conservative society. Ayouch describes their performances as captivating and almost hypnotic, capable of transforming even the most conservative audience members, triggering a complex mix of admiration and disapproval, a testament to the deep-rooted cultural resonance of their art.

This deep dive into the lives of marginalized figures is a recurring theme in Ayouch’s filmography. From street children in ”Ali Zaoua” to oriental dancers in ”Whatever Lola Wants” and the controversial portrayal of prostitutes in ”Much Loved,” banned in Morocco for its explicit content, Ayouch consistently confronts difficult subjects. His commitment extends beyond fiction, with documentaries like ”My Land” focusing on Palestinian refugees and his active involvement in organizations promoting cultural diversity and establishing cultural centers in impoverished areas. Ayouch’s work is not merely observation; it’s an intervention, a challenge to societal norms, and a platform for the voices often silenced.

Ayouch’s social activism is deeply personal, rooted in his upbringing with a single mother who instilled in him a strong sense of resilience and a keen awareness of the struggles faced by women and minorities. He credits his mother for inspiring his focus on marginalized communities, understanding that while women often face greater obstacles, their strength and perseverance can overcome them. This personal connection fuels his passion for telling stories that expose social inequalities and challenge conventional narratives. While meticulous research, like the three years spent with street children before filming ”Ali Zaoua,” is his usual approach, ”All Loves Touda” emerged from a more character-driven process, inspired by the personal stories of the sheikhas he encountered.

Ayouch expresses concern for the future of sheikhas in Morocco, many of whom have abandoned their traditional art form for more commercially viable popular music. He sees them as crucial figures in Moroccan culture and history, unfairly diminished in status. ”All Loves Touda” is not just a film; it’s a reclamation, an attempt to restore the respect and recognition these artists deserve. The film’s title, tinged with irony, hints at the conditional nature of societal acceptance, challenging the audience to confront their own prejudices and recognize the inherent worth of individuals who dare to defy expectations and choose their own paths. Ayouch’s film serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of art as a tool for social commentary, cultural preservation, and ultimately, human connection.