The relentless acceleration of modern life has warped our perception of time, transforming it into a weapon against both humanity and nature. If the Earth’s lifespan were compressed into a single year, humans would emerge in the final minutes of December 31st, with industrialization occurring a mere two seconds before midnight. This staggering perspective underscores the brevity of our industrialized existence and the profound impact we have had on the planet in such a short time. This impact manifests not only in overt violence and conflict but also in the insidious, pervasive violence inflicted upon our environment and our very selves through the relentless pursuit of speed and efficiency. The past year, the hottest on record, serves as a stark reminder of the ecological devastation we are wreaking, with rainforests disappearing at an alarming rate and fertile topsoil, essential for food production, being eroded and paved over. This ecological destruction, coupled with the accelerating pace of life, represents a form of violence that, though less visible than traditional warfare, is no less damaging.

The pervasive nature of this ”slow violence,” as termed by Rob Nixon, is particularly insidious. It permeates our bodies, manifesting as undiagnosed illnesses and cellular mutations, especially within vulnerable populations. Unlike the dramatic narratives of war, this slow violence remains largely invisible, escaping the grand narratives of victory and defeat. Its effects, however, are devastatingly real, contributing to a growing sense of unease and disquiet that pervades modern life. This unease is further amplified by the increasing speed of our daily existence. Our attention spans have plummeted, with the average person now able to focus for a mere 40 seconds, a significant decline from just two decades ago. This dwindling attention corresponds with a rise in the consumption of accelerated media, with podcasts, audiobooks, and YouTube videos often consumed at increased speeds, further reinforcing the societal obsession with speed. This constant acceleration, as described by the late anthropologist Thomas Hylland Eriksen, has become our overriding ideology, a pervasive and addictive force that demands ever-increasing velocity.

This accelerating pace of life has profound implications for our relationship with knowledge and information. As Hartmut Rosa argues, knowledge loses its relevance at an accelerating rate, requiring constant effort simply to stay current. We are trapped on a downward-sloping treadmill, perpetually in motion to avoid being left behind. Ironically, despite the proliferation of time-saving technologies, we find ourselves increasingly time-poor, perpetually chasing a phantom of efficiency. Stress becomes the dominant affliction, the leading cause of sick leave, a testament to the dissonance between our technological advancements and our lived experience. This ”time poverty,” as explored by Jacob Needleman, reflects a deeper metaphysical crisis. Our relationship with time, he argues, is fundamentally a reflection of our relationship with ourselves and the meaning of our lives. Yet, instead of confronting this existential dilemma, we resort to medicalizing and psychologizing the issue, diagnosing conditions like ”dyschronometria” and ”chronophobia” as if they were mere physiological malfunctions, rather than symptoms of a deeper societal malaise.

This relentless pursuit of speed and efficiency is not a neutral force but a form of violence against the natural rhythms of life. The traditional mechanistic view of biology, which saw organisms as machines capable of being pushed to ever-faster speeds, is increasingly being challenged by a new understanding of biological systems. This emerging ”poetic ecology,” as envisioned by Andreas Weber, emphasizes the importance of subjectivity, feelings, and meaning in all life forms. This perspective reveals the inherent violence of our obsession with speed, highlighting its incompatibility with the natural world. Natural processes unfold at their own pace, resistant to artificial acceleration. Pregnancy, sleep, and the formation of fertile soil all operate on timelines impervious to our desire for speed and efficiency. Attempting to force these processes leads to breakdown, whether in human bodies, ecosystems, or the planet itself. The relentless drive for speed is not just destructive; it is fundamentally unnatural.

The modern conception of time, with its emphasis on quantification and measurement, emerged as a tool of power and control during the Industrial Revolution. Prior to industrialization, work was measured not by time but by the completion of tasks, each with its own unique rhythm. The advent of machinery, however, demanded the standardization of time, transforming it into a commodity that could be bought and sold. Time became money, severing the connection between individuals and the tangible results of their labor. This shift required the widespread indoctrination of workers into the new time paradigm, with schools playing a crucial role in instilling the discipline of clock time. This resulted in increased productivity but also in the homogenization and alienation of labor. The factory, with its regimented schedule and constant surveillance, became the embodiment of this new temporal order.

The obsession with measuring and optimizing time reached its zenith with the introduction of the stopwatch and the rise of Taylorism. Frederick Taylor’s scientific management system, with its focus on breaking down tasks into minute, measurable units, transformed the nature of work. The Time Measurement Unit (TMU), representing 1/28 of a second, became the ultimate expression of this fragmented and quantified view of time. The assembly line, a symbol of modern industrial production, stands as a stark example of the dehumanizing effects of this temporal regime. Instead of questioning the inherent violence of this system, we find ourselves struggling to manage the fragmented remnants of our time, juggling work time, overtime, leisure time, screen time, and ”quality time,” all while anxiously awaiting the arrival of our next delivery, tracked in real-time on our mobile devices. This constant quantification and fragmentation of time erode our ability to experience the present moment, leaving us perpetually distracted and disconnected.

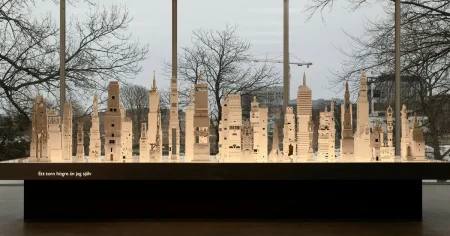

In contrast to this fragmented and commodified view of time, the Sabbath offers a profound alternative. Abraham Heschel described the Sabbath as a ”palace in time,” a sanctuary from the relentless demands of the workweek. Unlike other holidays tied to natural cycles, the Sabbath is a purely human construct, a weekly reminder of our place within creation. On this day, we are called to cease from our labors and contemplate our role not as creators but as created beings. This distinction between sacred and profane time is essential for maintaining a balanced and sustainable relationship with the world. The Sabbath offers a respite from the tyranny of speed, an opportunity to reconnect with ourselves, our communities, and the natural rhythms of life. Perhaps by embracing this ancient practice, we can begin to heal our fractured relationship with time and reclaim its inherent sanctity.