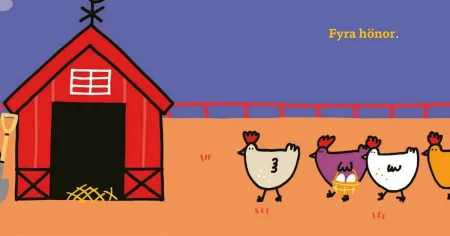

Munro Leaf’s ”The Story of Ferdinand,” a seemingly simple tale of a bull who prefers flowers to fighting, became a global phenomenon almost overnight. Its journey from a 40-minute writing exercise to an Oscar-winning Disney film, a cherished Christmas tradition in Sweden, and a modern-day queer icon, is marked by both unexpected success and complex interpretations. Leaf, a Harvard-educated writer and publisher in his 30s, penned the story in 1936, reportedly to showcase the talents of his illustrator friend, Robert Lawson. Inspired by a real-life bull who refused to fight, Civilón, Leaf crafted a narrative that resonated far beyond his initial intentions.

The book’s immediate success fueled a “Ferdinand fever,” with merchandise, branding opportunities, and a Disney adaptation quickly following. In 1938, Disney secured the rights and released the animated short, which won an Academy Award the following year. Leaf became a celebrity, giving interviews and enjoying the whirlwind of his creation’s popularity. Disney’s adaptation cleverly incorporated elements of Lawson’s original illustrations, like the corks hanging from the cork tree, further cementing the book’s visual appeal. The international market embraced Ferdinand as well, with the book being translated and published in numerous countries, including Sweden in 1938-39 where it was met with enthusiastic acclaim.

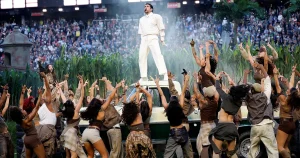

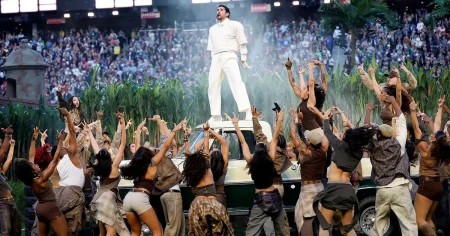

”The Story of Ferdinand” arrived in Sweden during a time of global uncertainty and rising tensions leading up to World War II. The gentle bull, who preferred the peaceful fragrance of flowers to the violence of the bullring, provided a stark contrast to the prevailing atmosphere of anxiety and conflict. Ferdinand was embraced by the Swedish public, becoming a symbol of peace and tranquility in a world increasingly dominated by aggression. He was featured in marketing campaigns, theatrical productions, and even a skating gala, solidifying his presence in Swedish popular culture. His debut on Swedish television in 1971 cemented his place in the nation’s Christmas traditions, despite an attempt in 1982 to replace him with another classic tale. The public outcry forced television executives to reinstate Ferdinand, showcasing his enduring appeal.

The simple story of Ferdinand became intertwined with the complex political landscape of the time. Published just after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the book was interpreted as a political statement, despite Leaf’s insistence that it was merely a humorous tale. It was banned in Franco’s Spain and Nazi Germany, seen as a potential threat to their ideologies of war and aggression. The left wing, on the other hand, viewed Ferdinand’s pacifism as a problematic stance in the face of fascism’s rise. Leaf found himself caught in the crossfire, criticized for both promoting pacifism and satirizing it. This multifaceted reception underscores the power of simple stories to become imbued with diverse and often conflicting meanings, reflecting the socio-political context of their time.

Ferdinand’s pacifism also resonated with the changing social values of the 1970s. His rejection of violence and embrace of peaceful contemplation aligned with the anti-establishment sentiments and calls for peace that characterized the era. In a secularizing Sweden, Ferdinand, with his message of peace and tranquility, even assumed a quasi-religious significance, offering an alternative to traditional Christmas narratives. His image as a gentle giant, unwilling to participate in the aggression of the world, embodied the values of a neutral welfare state. This further reinforced his status as a cultural icon, embodying the ideals of peace, compassion, and non-conformity that resonated with the Swedish public.

Beyond his political and social interpretations, Ferdinand also became a symbol of non-conformity and, more recently, a queer icon. His rejection of traditional masculine ideals, preferring flowers to fighting, challenged societal expectations of gender roles. In the 1930s, this led to concerns about his perceived effeminacy, even prompting a satirical song mocking his pacifistic nature and ascribing stereotypically feminine traits to him. However, this same non-conformity is what resonates with audiences today, celebrating individuality and self-acceptance. Ferdinand’s enduring popularity demonstrates the evolving interpretation of his character, transforming him from a figure of controversy to a symbol of embracing one’s true self, irrespective of societal norms. His quiet defiance, his preference for peaceful contemplation, and his unwavering commitment to his own nature, all contribute to his enduring appeal as a beloved character and a timeless message of self-acceptance.