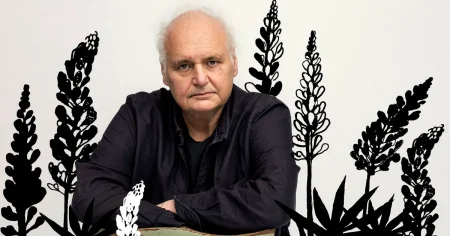

Erik Åsard’s ”Hitler’s Path to Power: The Weimar Republic from Democracy to Dictatorship” explores the unsettling question of how a sophisticated nation like Germany could succumb to the allure of a demagogue like Adolf Hitler. Åsard uses the hypothetical scenario of Hitler escaping to Austria after the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923 to highlight the role of contingency in history, prompting the reader to consider how different choices might have averted disaster. The book then embarks on a comprehensive examination of the Weimar Republic’s decline, offering a concise and engaging narrative that avoids excessive detail while providing insightful analysis. Åsard argues that the republic’s demise was not inevitable, emphasizing the agency of individuals and their capacity to influence the course of events. He suggests that with greater foresight and resolve, key figures could have prevented the catastrophic chain of events that led to Hitler’s ascension.

Åsard places significant blame on the coterie of conservatives surrounding President Hindenburg, individuals like von Papen and von Schleicher, who maneuvered within a power vacuum and ultimately handed Hitler the chancellorship, believing they could control him. Åsard underscores the folly of their decision, highlighting how Hitler didn’t seize power but rather received it as a gift. However, while acknowledging the gravity of their miscalculation, Åsard also argues that their ability to make such a decision stemmed from a more fundamental flaw: the erosion of democratic processes that had already marginalized the parliament. This allowed the group of military figures, monarchists, and other intriguers to gain legitimacy and power. The author contends that focusing solely on the immediate actors overlooks the broader context of widespread disillusionment, resentment, and despair that permeated German society.

The book delves into the deep-seated trauma of World War I, the economic hardships faced by a generation of unemployed men, and the pervasive mistrust of the democratic system, which was perceived as a source of division rather than order. Åsard points to the escalating political violence, with numerous deaths occurring during election cycles, as evidence of the deep societal fractures. While Hitler never achieved a majority vote, he benefited from the widespread support for anti-democratic parties, which garnered 57% of the vote in 1932, creating the fertile ground for Hindenburg’s circle to operate. This widespread disillusionment with democracy paved the way for figures like Hindenburg and his inner circle to gain influence and ultimately make the fateful decision to appoint Hitler.

The central lesson Åsard draws from this historical analysis is the importance of robust and transparent accountability systems to constrain the power of individuals, however well-intentioned they may seem. Without such systems, he argues, decisions are susceptible to being influenced by personal biases, self-interest, or even trivial circumstances. The seemingly insignificant incident of a broken-down car preventing Hitler’s escape, as highlighted at the beginning of the book, serves as a stark reminder of the role contingency plays in shaping history and the potential for seemingly small events to have far-reaching consequences. He emphasizes the need for constant vigilance and active participation in democratic processes to prevent their erosion and the potential rise of authoritarianism.

The book’s relevance extends beyond historical analysis to contemporary concerns about declining trust in democratic institutions. Åsard draws parallels between the anxieties of the 1930s and the present day, warning against the allure of charismatic leaders who promise simple solutions to complex problems. He argues that in times of uncertainty and crisis, clinging to democratic principles is paramount, as succumbing to the temptation of authoritarianism only exacerbates existing problems. The rise of populist leaders in recent times underscores the book’s message that the hard-won lessons of the 20th century must not be forgotten.

In conclusion, ”Hitler’s Path to Power” offers a compelling account of the Weimar Republic’s downfall, emphasizing the confluence of factors that enabled Hitler’s rise. Åsard’s analysis goes beyond simply recounting historical events, providing valuable insights into the fragility of democracy and the importance of safeguarding its institutions. By highlighting the role of both individual choices and broader societal forces, the book serves as a timely reminder of the constant vigilance required to protect democratic values and prevent history from repeating itself. It serves as a cautionary tale, not just about the specific events that led to Hitler’s rise, but also about the dangers inherent in abandoning democratic principles in times of crisis, a lesson that resonates powerfully in the 21st century.