Angela Merkel, in her newly released memoirs, stands firm, expressing no regrets about her decision to phase out nuclear power in Germany. She even suggests she should have done it sooner, dismissing criticisms that the move increased Germany’s dependence on Russian gas and weakened its security and climate policies. However, despite her protestations, her legacy is increasingly defined by this perceived naive relationship with Russia, a narrative shaped not by herself but by the ongoing political discourse. Political legacies, after all, are written by others, and the post-political life, even for a 16-year chancellor, far outweighs the time spent in the spotlight.

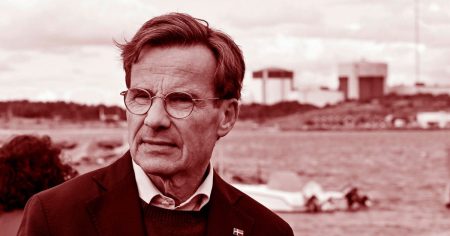

This raises the question of whether the current Swedish government, led by the coalition of Christian Democrats and Moderates, understands this dynamic. Their intense focus on the next political battle seems to blind them to the potential repercussions of their ambitious nuclear power plans. Just as Merkel’s Russia policy has become her defining (and negative) legacy, the Swedish government’s gamble on nuclear power could become their own defining misstep. Their unwavering belief in the ease of implementing a complex nuclear program in Sweden, despite the struggles faced by other nations, appears to be based on little more than optimistic projections.

The Swedish government’s plan involves building ten new nuclear reactors within the next two decades, with the first groundbreaking scheduled before the next election. Their proposed model, outlined in a recent investigation, involves state-funded construction followed by a customer-funded price guarantee. This proposal has been met with widespread criticism, even from within the government’s own ranks, due to its unrealistic nature and potential financial burdens on taxpayers. The plan effectively eliminates incentives for investment in other renewable energy sources, like wind and solar, at a crucial time for energy diversification and technological advancement. Furthermore, the government’s confidence in building ten reactors swiftly and efficiently seems misplaced, considering the protracted and costly experiences of other countries with similar projects.

Finland’s recently completed reactor took 17 years to build, with plans for a second reactor abandoned due to the difficulties encountered with the first. Similarly, the UK’s construction of two reactors has faced years of delays, forcing the government to extend the life of existing reactors. The costs associated with these projects have also spiraled out of control. The UK’s project is now estimated to cost 260% more than initially projected, totaling over 600 billion kronor for just two reactors. France’s experience with its latest reactor construction was even more dramatic, with final costs quadrupling the initial estimates. Despite these cautionary tales, the Swedish government remains steadfast in its belief that they can avoid such pitfalls.

This unwavering optimism appears to be causing friction within the governing coalition. While the Christian Democrats, Liberals, and Sweden Democrats are eager to commence construction, Finance Minister Elisabeth Svantesson and her department are applying the brakes. This difference in approach is not merely about “Moderate timidity in the face of criticism,” as some suggest, but rather reflects a more pragmatic understanding of the long-term implications of such a massive undertaking. Svantesson, a self-proclaimed admirer of Margaret Thatcher, is understandably hesitant to be associated with what could become the largest planned economy project – and potentially the biggest economic failure – in Swedish history.

The government’s apparent belief that their nuclear plan will become ”irreversible” for future administrations raises concerns about their long-term political strategy. Locking future governments into a potentially flawed and costly energy policy based on generous subsidies to a few large companies, while simultaneously stifling competition and innovation in other energy sectors, could prove politically disastrous. This strategy seems particularly ill-advised for a government whose sole answer to the climate crisis is nuclear power, especially given their repeated assertions that voters should not bear the brunt of the green transition. The potential legacy of this nuclear gamble – a financially burdensome, environmentally questionable, and politically damaging outcome – is hardly a desirable one.