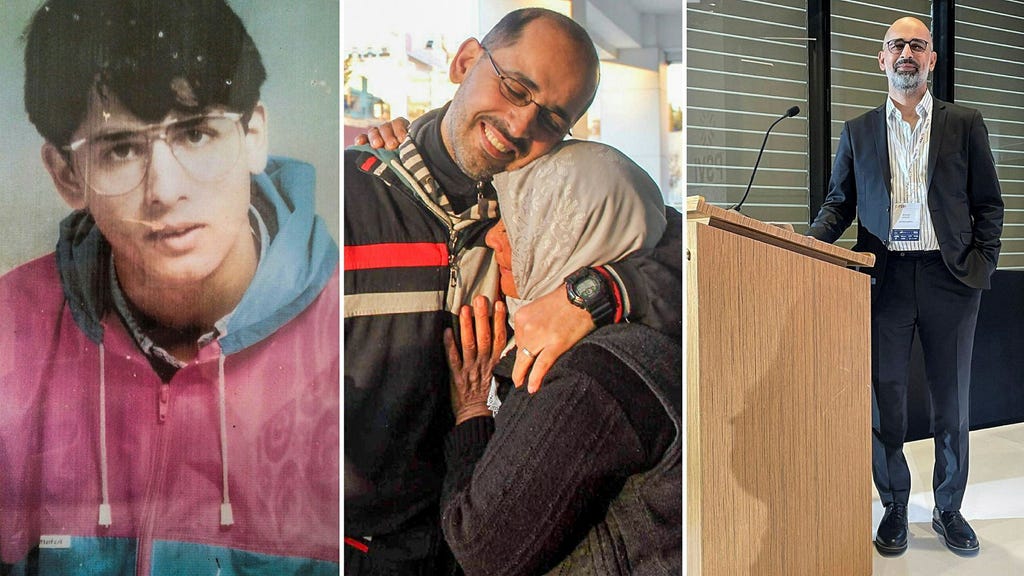

Riyad Avlar, a 50-year-old Arabic-speaking Turk with roots in the formerly Syrian province of Hatay, found himself entangled in the tumultuous political landscape of Syria in the 1990s. His initial journey to Damascus was driven by academic pursuits, a desire to delve into the region’s complex history at Damascus University. However, his curiosity and correspondence with friends back in Turkey about the atrocities committed by the then-Syrian President Hafez al-Assad, particularly the Hama massacre, led to his arrest in 1996. Accused of collaborating with a foreign country to incite aggression against Syria, Avlar spent 15 years in prison, largely cut off from the outside world, without legal representation or contact with his family. His ordeal highlights the oppressive nature of the Assad regime and its suppression of dissent.

After enduring over two decades of imprisonment, including a significant period within the infamous Saydnaya Prison, Avlar was finally released in 2017. The Syrian revolution, which had ignited in 2011, had drastically altered the political landscape during his incarceration, filling the prisons with even more political detainees. Driven by a desire for justice and accountability, Avlar co-founded the Association of Detainees and the Missing in Saydnaya Prison, dedicating himself to the cause of those who suffered similar fates. With the recent fall of the Assad regime and the liberation of Saydnaya, Avlar held onto the hope of finding former inmates alive and bringing the perpetrators of the regime’s atrocities to justice. However, the reality he faced was far more complex and disheartening.

The liberation of Saydnaya Prison, while a momentous event, was marred by the chaotic actions of initial responders. Civilians, though well-intentioned, rushed into the prison before organized teams like the White Helmets could arrive. This resulted in the destruction and loss of vital evidence, including documents, digital records, and surveillance footage that could have been crucial in holding the Assad regime accountable for its crimes against humanity. The chaotic scene at the prison underscores the challenges of preserving evidence in post-conflict scenarios and the potential loss of crucial information in the pursuit of immediate liberation.

Hassan al-Ahmad, a 28-year-old volunteer with the White Helmets, participated in the Saydnaya rescue operation. He described the grim atmosphere within the prison, permeated by a stench he couldn’t quite place—a combination of burned materials and possibly the lingering odor of death. The White Helmets’ systematic search, including the use of trained dogs and specialized equipment, yielded no hidden cells or additional prisoners, dispelling rumors that had circulated among Syrian families desperate for news of their missing loved ones. While they discovered physical documents dating back to 1992, the absence of digital records hindered efforts to compile comprehensive evidence of the regime’s abuses.

The absence of secret cells contradicted widespread rumors and the hopes of countless families seeking their missing relatives. Avlar, drawing on his own experience within the prison, confirmed the absence of such hidden areas. He described a period of relative freedom within Saydnaya in 2008, allowing inmates to move between cells, suggesting that the regime had no need for concealed spaces. Following an inmate uprising demanding fair trials and improved conditions, the regime’s response was brutal, increasing executions after sham trials, particularly after the 2011 revolution.

The discovery of over 50 bags containing burned bodies near Damascus airport added another layer of horror to the unfolding narrative. Coupled with the expectation of finding mass graves, these grim findings hinted at the true extent of the regime’s brutality. Avlar’s firsthand account of witnessing guards randomly killing prisoners with iron pipes as a form of intimidation further cemented the image of Saydnaya as a place of systematic torture and murder. He lamented the destruction of evidence within the prison, criticizing those who fueled false hopes about potential survivors in hidden cells. He stressed the importance of focusing on supporting survivors and the families of the dead and missing, while also seeking justice through the meticulous collection and preservation of any remaining evidence. The focus now shifts to caring for the liberated, supporting the bereaved, and pursuing justice for the countless victims of the Assad regime.